There are two historic cemeteries in the Jewellery Quarter; Key Hill and Warstone Lane. They are the final resting place of over 150,000 people, all with a story to tell. The Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham and the British Isles as a whole are entwined with the history of the British Empire and we have traced some of those links. Learn about politicians, industrialists, soldiers and migrants as we trace some of their colonial connections.

The research for this tour was done by Rahma Mohammed and the tour was delivered by Rahma Mohammed and Zak Saleh in November 2021, and was developed in partnership with Beatfreeks and Legacy West Midlands.

This self guided trail, with audio and transcripts, will help you to recreate this tour at your own pace, either online or while visiting the cemeteries.

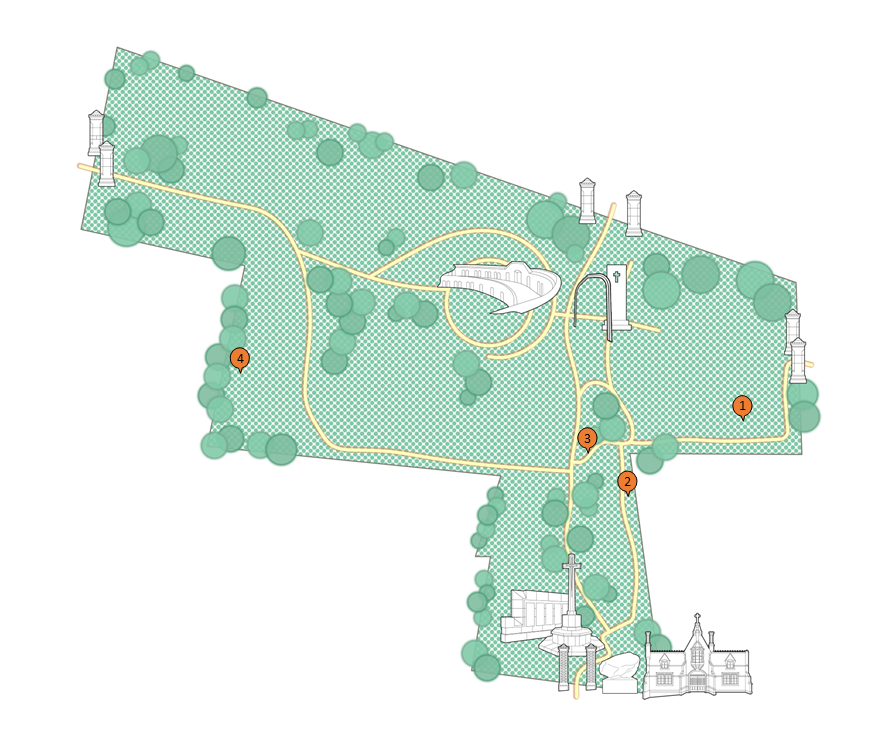

Warstone Lane Cemetery

1. Warrulan

Transcript

Warrulan died on the 23rd October 1855 from pneumonia. He was an Aboriginal Australian boy brought to England in 1844 by Edward Eyre, who was the son of an English vicar and an explorer of the South Australian landscape. In 1841, Edward Eyre became the Resident Magistrate and Protector of Aborigines for the Moorundie region, which is located near the Murray River in South Australia. As Moorundie was the first European settlement on the Murray River, Edward Eyre needed the help of an Aboriginal Australian man named Tenberry. Tenberry, who essentially operated in the role of a Chief, acted as a guide and used his influence to ensure that tensions did not rise between the settlers and Indigenous population. Warrulan was Tenberry’s son, making it all the more significant that Edward Eyre chose to bring him to England. It was reported that when Warrulan left, Tenberry and 200 other people from Murray River went to Adelaide to wave goodbye to him and inspect the ship before it left.

In January 1846, Warrulan and another Aboriginal boy called Pangkerin were taken by Edward Eyre to meet Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in Buckingham Palace. A newspaper article was written in the Illustrated London News about this visit. There were details about the two boys, such as Warrulan and Pangkerin both seeming to be between the ages of 8 and 10 and that they were ‘well-formed, active, and intelligent.’ The colour of their skin was described as ’black, or very dark copper’, with the description also including reference to their hair, eyes and teeth. Both boys were also said to be disappointed that there was not more of a fanfare to the Queen.

In this article, justifications were also offered for why Aboriginal Australian boys were brought to England. They shared hopes that by taking Warrulan and Pangkerin, it would in some degree mitigate ‘the evils’ that had been inflicted on Australia due to colonialism. The article also states that although Aboriginal Australians were not too advanced in civilisation, they did have a natural intelligence and ‘an equal capacity for improvement’.

Edward Eyre agreed with this ability of improvement as he brought Warrulan over to England in the hopes of ‘civilising’ him. The journey of Warrulan once he reached England reveals how they attempted to do this. When Edward Eyre became the Lieutenant Governor of New Zealand in 1847, he placed Warrulan under the care of Thomas Hodgkin, who had founded the Aborigines’ Protection Society in 1837. In 1847, Warrulan attended agricultural school in Oxfordshire where he learnt farming and horticulture and was introduced to Christianity. By the time he finished school, Warrulan became known as Edward. In February 1852, he went to stay with Thomas Dumbleton in Banbury. A member of the Aborigines’ Protection Society called James Cadbury supervised the moral education and improvement of Warrulan when he was at Banbury. He also sorted out a position for Warrulan to work in Birmingham at Middlemore Saddles in March 1855. Warrulan spent his summer break from this job at Thomas Hodgkin’s residence. On the journey back, Warrulan became ill, supposedly because someone on the train left a window open.

The Aborigines’ Protection Society wrote about Warrulan’s death, noting that when he was sick, Warrulan spoke about returning to Australia as he wanted to tell his father about how good Christianity had been to him. For a long time, Warrulan had wanted to send a Bible to his family as he had found it a source of comfort whilst separated from them. The intention behind Warrulan coming to Birmingham was that he was to continue working on his improvement before his expected return to Australia. Heartbreakingly, even if Warrulan had wanted to return to his family back in Australia, his father and many members of his community had already died by the time of his own death. However, Warrulan was never told of this because the Aborigines’ Protection Society thought that it was the more considerate approach.

To the Aborigines’ Protection Society, Warrulan seemed to be a model Christian student, however in the process of getting him to their standard, they had inflicted distressing harm on the Aboriginal Australian community. It was a colonial perspective that made Edward Eyre believe that he could ‘civilise’ Warrulan by bringing him over to England and it was the same colonial thinking that made the Aborigines’ Protection Society focus on Christianity.

We hope that in the near future, members of the Aboriginal Australian community who live in the area that Warrulan was from, may be able to visit his grave in the Jewellery Quarter. They wish to conduct a ceremony so that at least his spirit is able to return home.

Learn more about Warrulan by watching our film 2 Visions 2 Legacies.

2. Major Edward Berry Byrch

Transcript

Major Edward Berry Byrch died on Monday the 14th of July 1890, but his cause of death is unavailable. He was part of the Royal Marines Light Infantry where he became a Major and his last act of service was the Egyptian Campaign in 1882.

When the Suez Canal opened in 1869 Egypt became very important to the British as there was now a new route from Europe to the Far East that could save time and money. By 1869 Egypt had also benefitted from years of investment in irrigation, railways, cotton plantations and school with a lot of it coming from France and Britain but by 1876 the ruler, also known as Khedive, Ismail Pasha had accumulated debts of almost £100 million. The debt crisis saw the intervention of the French and British in the treasury, customs, railways and ports of Egypt.

With this loss of Egyptian sovereignty, a show of nationalism came form unpaid army officers under the leadership of Ahmad Urabi. By September 1881 Urabi and his followers had convinced the new Khedive Tawfiq to create a new government that was more nationalistic and in January 1882 Urabi became the minister of war himself.

The growing popularity of the nationalist movement worried Britain and France who were keen to maintain access to the Suez Canal and their financial investments. They sent a small joint fleet under the command of Admiral Sir F. Beauchamp Seymour to Alexandria which heightened tensions. Urabi ordered the strengthening of Alexandria’s defences and on 10th July 1882 Admiral Seymour demanded that Egypt remove these defences but they refused. Tensions also started to increase between France and Britain which led France to decide against armed intervention. Seymour was left in charge of 15 Royal Navy ships and gave the order for the bombardment of the forts around Alexandria with the first landing on 11th July. The bombardment lasted 10 ½ hours.

On 13th the land invasion began into the city of Alexandria which had already been partially destroyed by fire. On that same day Khedive Tawfiq sought British protection leaving Urabi as the leader of the Egyptian government. Fearing for the safety of the canal William Gladstone sent a force over to restore order and install a new administration. Over 400 royal naval ships were involved in securing the Suez Canal. However, Prime Minister William Gladstone was well-known for not wanting to get involved in imperial intervention so some historians wondered whether Seymour exaggerated the threat from Egypt.

In September 1882 a battle took place in Tel-el-Kebir. Because the desert around Tel-el-Kebir was extremely flat the Egyptian army had dug deep ditches and embankments as a form of defence. However to work around this the British attacked at dawn having travelled across the desert at night and after some intense fighting the Egyptians fled after an hour. The British made their victory march into Cairo whilst Urabi and his associates were taken prisoner and later exiled to Sri Lanka.

After 1882 although a Khedive remained in power the reality was that British had control and maintained a permanent British military presence to defend the Suez Canal. Although Egypt did not technically become a colony of Britain because of the British control over finances, government personnel and armed forces this period of time can been seen as the British occupation of Egypt.

After Major Edward Berry Byrch’s death he was interred with military honours and his funeral procession was accompanied by a mounted detachment of the 6th Carabineers and the Police Band which played the Dead March.

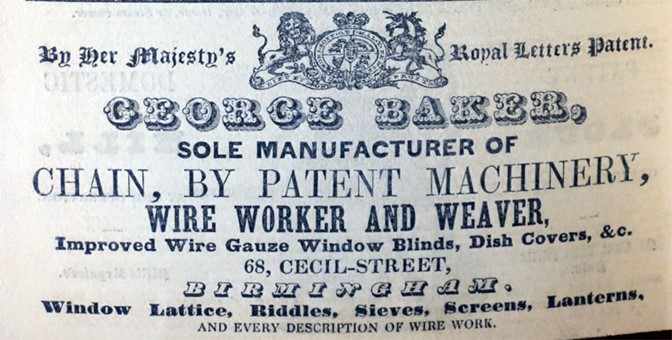

3. George Baker

Transcript

George Baker died on Saturday 9th February 1895 after he caught a chill. He came from humble beginnings as his dad died when he was really young and by the age of 7, he was left to his own resources. He had started off as an apprentice for a wire-making business alongside attending night-school education. He then became the head of Cecil Street Wireworks, which would end up being one of the largest wirework businesses in the world.

George Baker won a medal at the Great Exhibition in 1851 for the best display of wirework. The full name of the exhibition was ‘The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations’. The exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria on the 1st May 1851 and was open until the 11th October 1851, with a total of 6 million people visiting.

Most of the credit for the exhibition in 1851 has gone to Prince Albert, but the influence of Henry Cole should not be overlooked. Cole was inspired by the French ‘Industrial Exposition of 1844’ and took his idea of bringing this to the UK to Albert. A sense of national pride meant that they wanted the British version to be bigger than what the French could establish. The impressive iron and glass conservatory that housed this exhibition and was designed by Joseph Paxton came to be known as the Crystal Palace and was situated in Hyde Park. Its measurements were 564 metres long and 33 metres high. The glass was provided by the Chance Brothers, which was a glass-making business that was located in Smethwick.

The exhibition opened up and whilst it claimed to be a celebration of the world’s work, more than half of the 100,000 exhibits that were on display were from Britain or the British Empire, which made the exhibition more of a celebration of British manufacturing.

Initially, the admission price was £3 for gentlemen and £2 for ladies and these visitors would turn up in their carriages. However, from the 24th May 1851, the masses were allowed in for just a shilling. Factory workers would be sent by the bosses to visit the exhibition, school children went as part of their school trips and Thomas Cook put on special excursion trains. In this sense, the 1851 exhibition can be seen as a form of ‘public education’ and essentially a way of showing off what was considered to be the ‘Other’ in comparison to examples of British superiority. Getting working-class people involved with the colonial project was important and exposing them to the works displayed in the exhibition was one way of doing this. It was also an effective way of doing it as it did not threaten class-based hierarchies in the UK, with working-class people superior to those colonised but remaining inferior to the upper and middle-class in Britain.

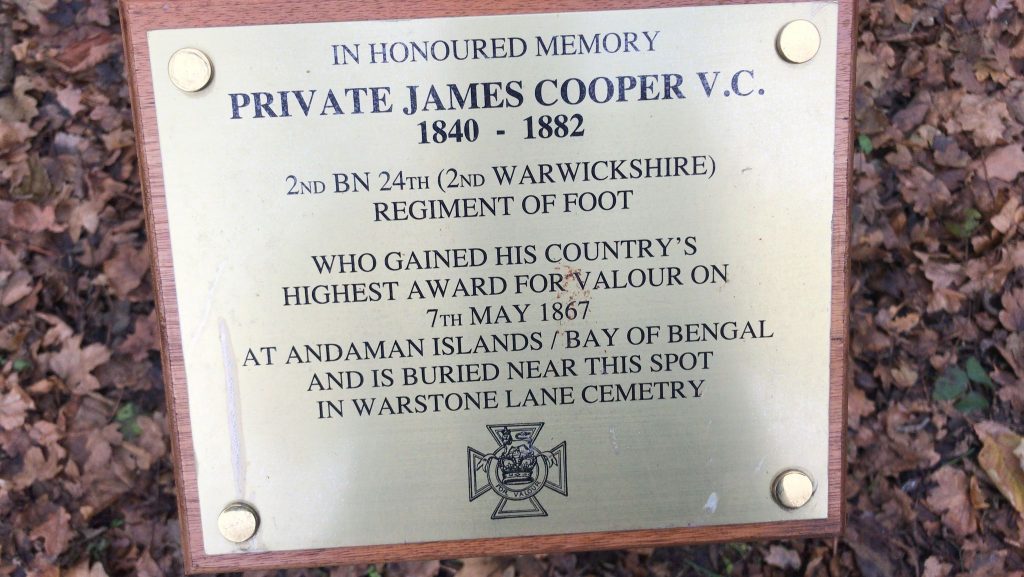

4. Private James Cooper VC

The grave of Private James Cooper is a public grave and no memorial stone survives (section P, plot 1428), but his resting place is now marked with a brass plaque.

Transcript

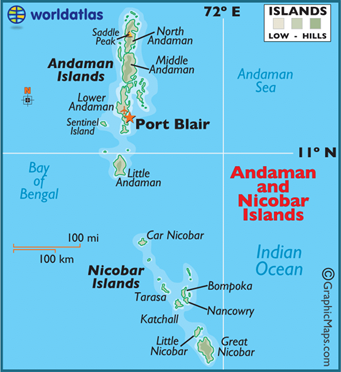

Private James Cooper died on the 9th August 1882 but his cause of death is unavailable. Little is known about Cooper until he joined the 2nd Battalion of the 24th Regiment of Foot and following his return to Birmingham after his army career he ended up in extreme poverty. One of the things that he had managed to accomplish in his life was that he awarded the Victoria Cross medal (VC) for his role in 1867 rescue on the Little Andaman Island.

First British contact with the Onge people of the Andaman Islands can be dated back to 1825. The British started contemplating occupation of the islands in the late 18th century and commercial and political reasons in the Indian Ocean convinced the British that there should be at least some partial occupation of the islands to gain the benefits of the agriculture and forest resources.

The first British settlement in the islands between 1789 and 1796 occurred at a time when people believed that the Andamanese were predisposed to natural aggression and cannibalism. These beliefs of Andamanese brutality only increased by the next settlement in 1856 coinciding with European adventurers and sailors coming into contact with the Indigenous people.

However, the claims of cannibalism did not hold up when properly inspected but it was a narrative that was useful to the colonisers as it was a familiar tool. The idea of cannibalism was used to ‘other’ certain peoples and benefitted the Europeans who wished to use it as evidence of their civilisation – although the use of savagery in the Andamanese context wasn’t so that they could ‘civilise’ the population but rather as a way to control and deal with any challenges they faced.

This became known as the Assam Valley Incident which has been identified as the precursor to a series of skirmishes that are sometimes referred to as the Onge Wars which took the lives of many Onge people who are indigenous to the island.

In response to the Assam Valley Incident a boat was sent to see if there were any survivors but all they could report back was that there was a piece of clothing on the shore.

A few days later the Kwang Tung was sent with British Officer in charge of the Andamanese, Mr Homfray, along with some local people to show the friendly intentions of the crew. However, this failed and they were attacked by the Onge people and were forced to retreat to their boats.

As the missing men were not located and the first expedition was a failure a larger expedition with a small military contingent went and landed on the 6th May 1867. Whilst fighting against the indigenous people they found a skull on the beach and 4 decomposing bodies.

Despite the Onge people trying to lure the British further inland the British stayed and tried to fight the indigenous people on the shore. Their rescue boat capsized and it was following this that the Assam Valley arrived with five men, including James Cooper, who rescued the British party and returned them to the Kwang Tung.

All 5 men were awarded the VC but not for bravery in action against the enemy, which it is usually awarded for, but for bravery at sea in saving life in a storm off the Andaman Islands.

Key Hill Cemetery

5. James Davey Rippingille

Transcript

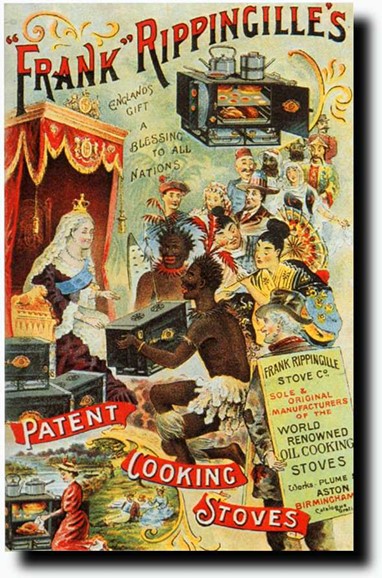

James Davey Rippingille died on the 26th March 1894. Alongside his father, Edward Alexander Rippingille, they both ran the Albion Lamp Company at Aston Road where they manufactured oil cooking stoves. Unfortunately when James Davey died, his father would die 3 days later which meant that the business went to James Davey’s wife, Eliza Rippingille. The success of the Albion Lamp Company encouraged imitators so in their adverts, they warned customers against buying oil cooking stoves from competitors. One of the companies that they named in these adverts was the Frank Rippingille Stove Company.

Unsurprisingly, James Davey Rippingille and Frank Rippingille were related. They both shared the same father, although they were from different marriages. Frank Rippingille also ran his stove company from Aston and in June 1896, he placed an advert in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph announcing that people could now buy shares in the company. The company needed extra investors as they wanted to carry on and extend the business further. It acknowledged the fact that the name Rippingille was widely associated with the oil stove cooking industry, whilst also stating that their specific business was expanding across the world. Showcasing the economic strength of the company, chartered accountants noted the growth in profits.

It was within this context that an advert for Frank Rippingille Stove Company was created in 1897. An initial look might see this advert as supporting the notion that the business was booming across the world. However, a deeper look reveals colonial tropes which are worth exploring.

Explicitly referenced in the advert with the words ‘England’s gift/ A blessing to all nations’, British industrial power was presented as a gift that the company was willing to share with the rest of the world. The pastoral idyllic landscape in the advert is a demonstration of how advanced Britain was as the stove was already in use. Furthermore, the queue of people not only pointed to an international demand for the stoves, it also depicted a relationship between the ruler and the ruled, and the coloniser and the colonised.

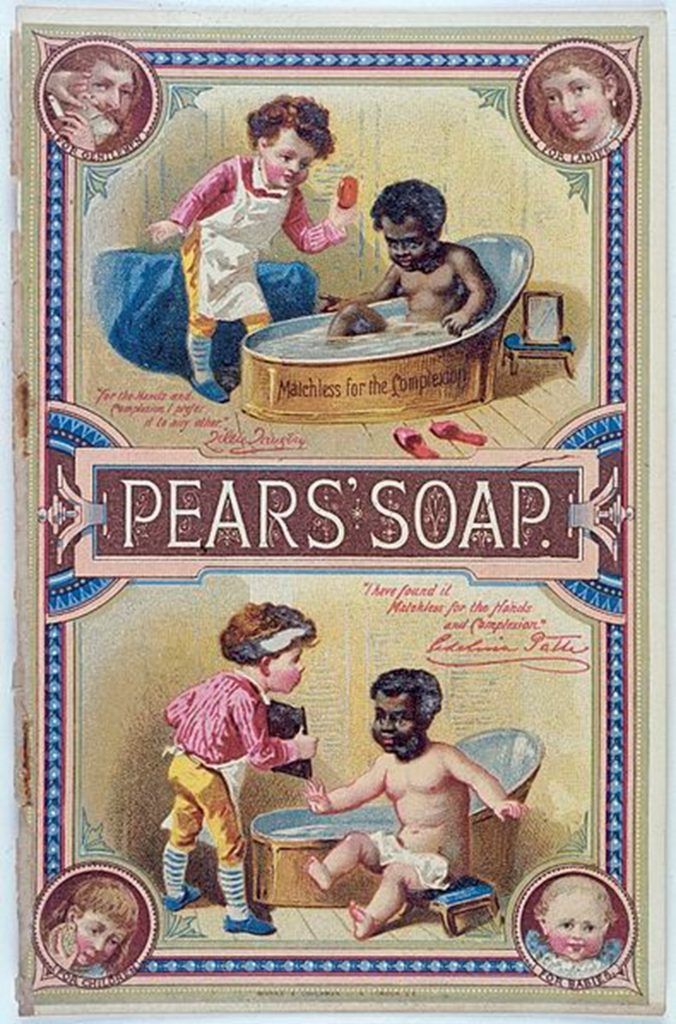

This advert is also significant because it responded to developments in the advertising industry that took place in the 19th century. The inclusions of caricatures of people beyond just Black people is one such example in the Rippingille advert. Advertisers had realised the potential value of the ‘racial Other trope’ and would create variations based off that, which included presenting people as uncivilised, non-Christian and oversexualised. As a result of this, advertising developed as an industry as they would look to the success of companies like Pear’s Soap and realise that this could be emulated with food, drinks and even stoves. These adverts presented Britain as superior and more advanced, and in the case of Pear’s Soap, demonstrated how whiteness was associated with purity.

(Wellcome Images)

It is important to recognise the contribution that visual advertising made in popularising colonial, racist ideology. By promoting household objects in these adverts, like an oil stove, it allowed this ideology to reach those who may not have been exposed to racial ideology present in books and plays. The adverts produced at this time all combined so that the colonial idea of British superiority could be cemented in the public’s mind as facts.

6. Joseph Chamberlain

Transcript

Joseph Chamberlain died Thursday 2nd July 1914 following health complications after a major stroke he had. He was the Mayor of Birmingham from 1873 to 1876. During that time Birmingham underwent a series of reforms that included bringing the gasworks and water supply in the city under municipal control and clearing the slums under the Birmingham Improvement Scheme in 1875. He became a MP in 1876 and he was the Secretary of State for the Colonies when the Second Boer War happened between 1899 and 1902.

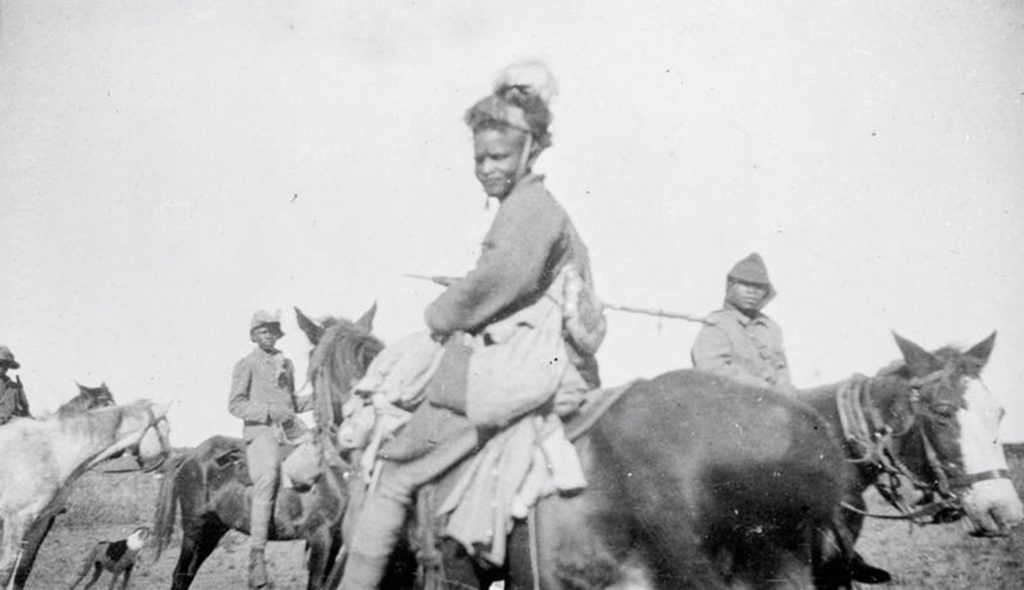

The war was fought between Great Britain and the 2 Boer Republics – the South African/Transvaal Republic and the Orange Free State. the Boers were white settlers in South Africa. This war is also known as the South African War to acknowledge that all parties, including black South Africans, were affected by the war.

The discovery of gold at Witwatersrand in 1886 and an alliance between the Transvaal Republic and Orange Free State made the British nervous that the Transvaal Republic were aiming for a united South Africa under Afrikaaners, which would threaten British supremacy and their ambitions to take control over the two republics.

Foreigners, also known as uitlanders – who were mostly British, were accepted reluctantly by the Boers as they needed all the help they could get in the gold mines and the British, including Joseph Chamberlain, were in favour of giving the uitlanders more voting rights so that the balance of power would be in favour of the British rather than the Boers.

The Boers rejected this proposal and negotiations weren’t going very far so the President of the Transvaal Republic, Paul Kruger, offered an ultimatum – that the British government had 48 hours to withdraw their troops from the borders of the two republics. When this never happened Britain went to war with the two allied republics.

During the war the British adopted a ‘scorched earth’ policy where towns and farmers crops were burnt and livestock wiped out. Concentrations camps were also set up where civilians were confined, especially women and children who had their houses burnt. This system expanded over 1900 as they believed that the fighters in the republics would be more likely to surrender if they couldn’t access food from their houses and would want to reunite with their family. The camps were poorly administrated with poor hygiene.

Black South Africans had fought on both sides of the war. The Boers used them as spies due to their knowledge of the terrain as well as for grooming horses, preparing food and being armed guards. The British tried to win Black South Africans over by portraying themselves as anti-racist and the Boers as cruel. For example, the British encouraged black South Africans to occupy Boer farms and their cattle. But once the British won the war they went from empowering them to disempowering them by disarming them and making them return the land and cattle and forcing them to leave urban areas. Black South Africans were also held in the concentration camps so that the Boer’s could not find another access to food but also as a way of gaining a labour force to work in the gold mines that were reopening in mid-1901.

Nearly 100,000 lives were lost in the war with more than 30,000 of that being British and Boer soldiers. In the concentrations camps around 20,000 black South Africans and approximately 26,000 Boer civilians had died.

The Peace of Vereeniging treaty in 1902 ended the independence of the Transvaal Republic and Orange Free State. Chamberlain visited South Africa after British victory and the Chamberlain Memorial Clock in Jewellery Quarter memorialises this visit.

The quote on the plaque reads: ‘We have shown that we can be strong and resolute in war; it is equally important to show that we can be strong and resolute in peace.’

7. Muslim Burials

Transcript

In Key Hill Cemetery, you can find the unmarked graves of Shadi Mohammed and Gluham Mohammed. They died, alongside three other victims, on Saturday 2nd November 1940 when sandbags collapsed in the air raid shelter they were sleeping in. Shah Sha, who survived the incident, told the inquest that they were in the habit of visiting the shelter every night to sleep. On the Friday night, they had arrived there at 7:00pm. He had stayed up talking until 11:30pm before being woken up at 6:00am in the morning to the sound of sandbags collapsing. He also told the inquest how he had to dig out Shadi Mohammed and his wife with his hands. Coroner Dr W. H. Davison ruled the 5 deaths as accidental, stating that ‘there [was] nothing to suggest that such a happening could have been anticipated and there was no warning that it was likely to happen.’

As Shadi Mohammed and Gluham Mohammed were referred to as Indians in the newspapers reporting on their death, it is worthwhile considering their migration story. Whilst we do not know much about their individual stories, we know that in 1932, the Indian National Congress survey of “all Indians outside India” estimated that there were 7,128 Indians living in the United Kingdom, which included students and professionals such as doctors. In 1939, only a year before this incident happened, the resident Indian population of Birmingham was recorded at 100. We can conclude that all the victims, which also included a British Jewish couple, were part of a small but growing migrant community in Birmingham. The fact that the victims all lived together in the same house at 9, Sutton-street suggests that this was a supportive, interlinked community.

This particular site in Key Hill Cemetery where Shadi Mohammed and Gluham Mohammed are buried is also important as they are buried next to a marked grave of another Muslim, Ghulam Hassam. Other potential Muslims next to these graves are Khir Dean and Mohamed Hussein Hassan. The burial records seem to indicate that this was an area set aside for Muslim burials in the 1940s. Key Hill Cemetery was a general cemetery, open to all creeds and denominations, and is unconsecrated land.

If there were was an Islamic burial that took place, there is a certain order which would have been followed. The first part is the washing of the body in a process known as ghusl. The body is then wrapped in a white shawl.

Following this, the funeral prayer known as the Janazah prayer, takes place. Typically held around midday, this prayer is well attended by those who knew the deceased, with the congregation normally asking for God’s mercy and forgiveness. Once the prayer has finished, the body is taken to the cemetery. This is a chance for members of the community who might not follow the Islamic faith to pay their respects. Traditionally, those who wish to do so will throw 3 handfuls of mud onto the coffin. Once this has been done, the coffin is then covered. The burial site is normally marked by a small plaque, rather than a grand headstone. Whilst we may not know how the Islamic burials happened in Key Hill, we have records showing the names of their officiating ministers, which suggests that some aspects may have been followed.

8. Councillor James Whateley

Transcript

Councillor James Whately died on Thursday 23rd November 1893 after a had a fall which led to pneumonia and pleurisy. He was associated with the Birmingham Liberal Association, and with his political background he had also come into contact with Joseph Sturge and Reverend Arthur O’Neill and also John Skirrow-Wright.

He was a part of the Birmingham Peace Society – in his obituary it said that he ‘was passionately fond of freedom and had a passionate hatred of oppression’, and the campaigns that were specifically mentioned that he was involved with were referring to the Afghan and Chinese Wars. which we have inferred that is in reference to the First Afghan War from 1839 -1842 and the First Opium War that was also fought from 1839-1842.

He and Reverend Arthur O’Neill would go around and put-up placards warning young men against being recruited because they felt that they were being sent to their deaths. Whilst these placards were quickly removed by police officers they would just put them back up. O’Neill felt that these actions ended up reducing the length of the war.

In the First Afghan War, India was critical for the British Empire so they were very eager to protect it from any encroachments by Russia. Afghanistan was in a strategic location between India and the Russian Empire so the British-owned East India Company were eager to have a pro-British Emir on the throne.

Emir Dost Mohammed was initially in favour of allying with the British but when they wouldn’t help him regain Peshwar he began entertaining the Russians which made him seem anti-British. By Spring and Summer of 1839 the British were able to start making headway so that they could replace Dost Mohammed with their preferred Emir, Shah Shuja who had ruled Afghanistan prior to Dost.

The British managed to storm the Ghanzi fort in July 1839 which was blocking their route to Kabul and this saw 200 British men killed or wounded and nearly 500 Afghan men killed. By August 1839 Shah Shuja was installed as Emir and the British left two brigades of troops and two political aides in order to keep the peace.

However, underlying tensions and resentment of the British made Shuja’s rules more difficult and growing unrest in Kabul led to a full blown insurrection in November 1841, led by Dost Mohammed’s son, Muhammed Akbar Khan, which saw the two political aides murdered.

By December 1841 the situation had worsened dramatically but the British had managed to negotiate an escape to India from Kabul and they set off on 6th January 1842 with 4,500 British and Indian troops and 12,000 camp followers.

However, on this retreat, over 16,000 were killed. The General who led the retreat over the mountainous terrain did not turn back to Kabul when he realised that they did not have enough food and fuel or their promised escort which contributed to the number of deaths.

This painting shows the massacred British, led by Elphinstone, who were trying to make their return from Kabul. The mountainous terrain, harsh weather and the weaponry of the Afghans are all reasons for why the British were overpowered.

By 13th January it seemed that everyone had been killed by Muhammad Khan and his troops with only one loan survivor and with the others being taken hostage. When Muhammad Akbar Khan had finished murdering the British in Kabul he turned his attention to Major-General Sir Robert Sale, to Jalalabad where the British had been strengthening the fort there. The British sent out the Army of Retribution to help the situation at Jalalabad and they would eventually defeat Muhammad Akbar Khan before reaching Kabul to rescue the 95 British hostages.

Following this the East India Company decided that occupying Afghanistan cost too much money and Dost Mohammed Khan who handed himself into British custody in November 1840 was quietly release and returned to Afghanistan where he reigned until his death in 1862.

This disaster also eroded morale within the Bengal Army who had the most casualties and started the feelings of discontentment that would eventually contribute to the Indian Mutiny in 1857.

Before the First Opium War fought between the British and the Qing dynasty, trade between China and the West took place within the Canton System based in the northeastern city of Canton which was the only place where the Chinese were open to trade with Foreigners. and only licensed merchants were allowed to trade. This has been taking place since 1757.

The Qing dynasty only allowed foreigners to trade in the Canton (Guangzhou) port and through licensed Chinese merchants.

At the start of the 19th century trade in Chinese goods such as tea, silk and porcelain were extremely lucrative for British merchants but the Chinese would not buy British products and would only sell their goods for exchange of silver, so a lot of silver was leaving Britain.

As a response the East India Company and British merchant smuggled Indian opium into China illegally and asked for payment in silver which they would then use to cover the cost of Chinese goods. But when the British East India Company lost their monopoly over British opium this made matters even worse and so they lowered their selling point so more people in China were able to buy opium. This led to millions of addicts in the country by 1840.

In order to stop this legal and illegal trade of opium the Chinese had banned the production and importation of opium in 1800 and banned the smoking of opium in 1813. . In May 1839 the Chinese forced the British to hand over their stocks of opium that were held at Canton and they destroyed it all which was the incident that sparked the conflict.

A series of skirmishes happened which led to serious fighting before an initial agreement was signed in January 1841 which made Hong Kong a British territory. The fighting continued to take place but with consecutive British victories the Chinese eventually realised they were overpowered and the war ended in August 1842. The Treaty of Nanjing in 1842 committed China to free trade, including the trade of opium, at multiple ports and the Chinese also had to pay reparations. Aspects of the treaty also included the fact that British citizens who lived in these treaty ports were subject to British laws, not Chinese laws. There was also a ‘most favoured nation’ clause which meant any rights that other foreign countries gained in China would also apply to Britain. Many British merchants, smugglers and the British East India Company had complained that China was out of touch with ‘civilised’ nations who practiced free trade and this war was seen by some as being a way to get China to open their markets.

From 1844 there was a system of treaties between China and western powers which allowed westerner to build churches and spread Christianity. For China the losses in the two opium wars (the second happened from 1856-60) and the system of unequal treaties weakened the legitimacy of the Chinese state.

9. John Skirrow Wright

Transcript

John Skirrow Wright was the Minister of Parliament for Nottingham when he died on Thursday 15th April 1880. It was recorded that he died from apoplexy, which is a stroke. Skirrow Wright was the president of the Birmingham Liberal Association group and was credited for its success as he had been with the Liberal Party for 25 years. He was also the President of the Birmingham Chamber of Commerce where he came up with the concept of postal orders to enable poor people, who didn’t have bank accounts, to buy goods by post.

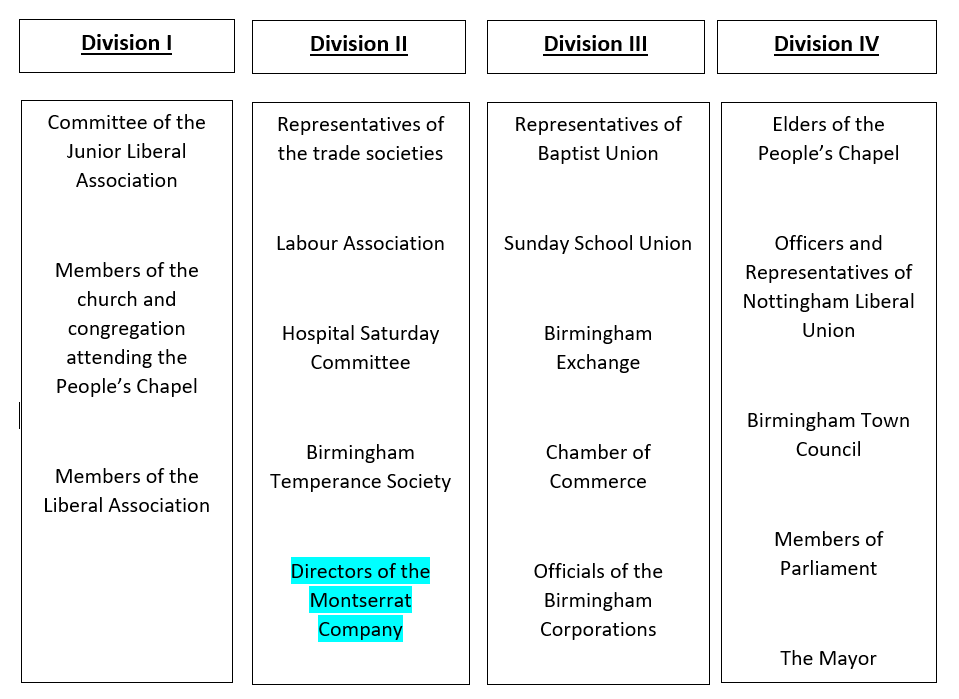

On the day of his funeral, certain groups and organisations were invited that were said to be associated with him during his life. The Montserrat Company were important enough that they were included in the funeral procession, in Division II to be exact.

The Montserrat Company was set up by Joseph Sturge who was a Quaker and known for his abolitionist stance against slavery. When the Imperial Abolition Act of 1833 was passed, there were 2 conditions attached to the Act. One condition was that slave owners received compensation and the other condition was that the freed slaves still had to work for another 7 years as apprentices in the apprenticeship system. This apprenticeship system saw freed slaves over the age of 6 work 45 hours per week with no pay.

For most abolitionists, when the Act of 1833 had been passed, they felt satisfied. However, Sturge didn’t and went to campaign against the apprenticeship system. Accompanied by Thomas Harvey, they ended up publishing The West Indies in 1837, a book which documented their travels around the Caribbean. The apprenticeship system would come to an end on the 1st August 1838, which meant that the freed slaves finally achieved ‘real’ freedom 3 years earlier than initially planned.

It was during this time that Joseph Sturge purchased his first estate on the Montserrat island in 1837. Nothing seems to have happened until 1857 when two more estates were brought by Joseph Sturge. His intention behind purchasing this land was because he wanted to show that you could have high levels of production with free, wage-earning, labourers. However, he died in 1859 before he could really put this to the test in Montserrat.

Despite his death, the Sturge family continued to have a presence in Montserrat, buying another estate in 1860. In 1869, the Sturge’s Montserrat Company was formally formed under Joseph Sturge II before becoming the Montserrat Company in 1873, who had their headquarters in Birmingham. Just before 1900, the Montserrat Company’s lime juice had almost become world famous, demonstrated by all the adverts that were placed in the papers.

If you look uncritically at the Montserrat Company, it can be viewed positively. In 1931, they actually boasted that they helped to develop a community of small landholders on the island. This positive outlook also works alongside a colonial theory which emerged after the emancipation of slaves. This theory suggested that following emancipation, there were two different types of colonies. If you were a colony that had a high density population, then the freed slaves were more likely to become estate labourers, like those who worked on the estates for the Montserrat Company. If you were a colony with a low density population, then you were more likely to have freed slaves become an independent peasantry. However, this theory is not necessarily true and obscures the more nuanced relationship that exists between land and labour.

After emancipation in 1838, labour still had to operate within power structures. The Sturge family had brought up a considerable amount of the land available in Montserrat, which left them in a powerful position. A critical approach can also encourage us to think about emancipation as an event that most likely happened with the end of apprenticeships in 1838 versus emancipation as a reality for the freed slaves. In this context, the Montserrat Company no longer seems as benevolent but rather it seems like it operated as a system of domination that forced labourers to work on the estates as the only way to avoid poverty.