Engraving of Constance Naden from ‘The Complete Poetical Works of

Constance Naden’ (Bickers & Son: London, 1894

Constance Naden was a unique and accomplished figure in the late nineteenth century who thrived in a range of pursuits such as poetry, science, and philosophy. Naden had an absolute refusal to stick within the confines of any intellectual or societal box. This determination is inspiring whilst her ability to excel in such an array of subjects is fascinating. In this blog, we take a brief look at Naden’s life and explore what made her such a distinctive voice in the Victorian era.

Early Life

Constance Naden was born on 24th January 1858 at 15 Francis Road, Edgbaston. She was brought up by her wealthy grandparents, Josiah and Caroline Woodhill, at Pakenham House, Edgbaston after her mother passed away a fortnight after her birth. Mr Woodhill was a retired jeweller who had once owned one of the largest wholesale goldsmith and jewellery businesses in the city. It was in Pakenham House where Naden began to make her way through her grandfather’s old library.

From the age of eight she attended a private day school run by unitarian sisters on Frederick Rd where she began to display a creative flair through flower painting and storytelling. Her love of painting continued after she left school at the age of seventeen, even getting one of her paintings, ‘Bird’s Nest and Wild Roses’ accepted by the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists in their Spring exhibition in 1878. This interest in flower painting can be seen later in some of her poetical works and on the front covers of poetry collections such as her posthumously published The Complete Poetical Works of Constance Naden (1894), which features an s-shaped flowered vine.

Poetry

In an article in The Speaker released after Naden’s death, Prime Minister W.E Gladstone named Constance as one of his favourite female poets, describing Constance Naden as one of eight British poetesses with significant prowess and command of language.

Constance Naden first published her work in 1877, in St. James’s Magazine. She would later publish Songs and Sonnets of Springtime, in 1881, which was dedicated to her grandparents.

After College, she published A Modern Apostle; The Elixir of Life; The Story of Clarice; and other Poems(1887). Within these, ‘Evolutional Erotics’ is arguably the most well-known of her sequences in which she deftly explores Darwinism in relation to romantic relationships. Naden’s comic poetry was often subversive, witty, and intrinsically tied to her scientific knowledge and desire to interrogate Victorian gender stereotypes.

As an example, take a look at ‘Natural Selection’ in which a male speaker watches ‘the Law of Selection at work’, as his romantic prospect picks, not him, but one of the ‘more dandified males’ to be her mate:

But there comes an idealess lad,

With a strut, and a stare, and a smirk:

And I watch, scientific though sad,

The Law of Selection at work.

(Stanza from ‘Natural Selection’, Complete Works, p.315.)

Constance Naden also used poetry to critique the restrictions placed upon women wishing to educate themselves. Naden’s poem ‘Love Versus Learning’ is humorous, turning a mocking eye to a male who has all of the opportunities to learn but doesn’t have a genuine thirst for knowledge. This contrasts with the narrator’s own interests in Latin and the Sciences which the male patronises:

He’s mastered the usual knowledge,

And says it’s a terrible bore;

He formed his opinions at college,

Then why should he think any more?

My logic he sets at defiance,

Declares that my Latin’s no use,

And when I begin to talk Science

He calls me a dear little goose.

(Stanzas from ‘Love Versus Learning’, the Complete Works p.89)

Constance Naden was a talented linguist, learning a range of languages such as French, German, Latin, and Greek. This competency in languages can be seen in her poetic translations, available to read in ‘The Complete Works’. As you can see, Naden was a multifaceted character, continuously interweaving her interests in poetry, science, and philosophy.

Education, Science, and Philosophy

Naden was a true polymath, interested in an array of scientific and philosophical topics.

In 1876, Naden met the philosopher Robert Lewins and was introduced to the theory of Hylozoism which states that all matter has life. Once converted to this theory, Naden developed this further with Lewis to form the theory of ‘Hylo-Idealism’, a philosophical position that we engage with the universe through our nervous system so it is through our material bodies that we understand reality. Over the years, Naden discussed many philosophical and scientific ideas with Lewis, first publishing on ‘Hylo-Idealism’ in 1881 in the Journal of Science and Knowledge. A lot of her ideas of ‘Hylo-idealism’ can be found in Induction and Deduction, 1890.

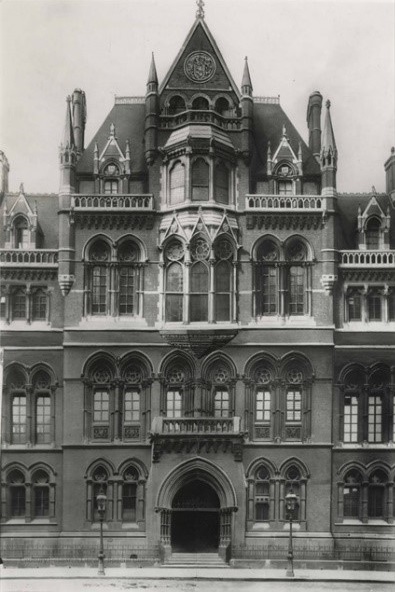

In 1879, Naden enrolled at the Birmingham and Midland Institute studying a range of subjects such as Botany, Language, and Art. From 1881 to 1887, Naden studied at Mason College of Science (now called the University of Birmingham). Here, she excelled in a range of scientific subjects including chemistry, zoology, and physics. She was an exceptional student, achieving first-class honours in all her exams and receiving many accolades for her academic output such as being the first woman to be awarded the Associateship of the College.

Naden was also very active in a range of academic societies; she edited the Mason College Magazine, was a member of the Birmingham Natural History Society, and was involved in debating within the College. She became increasingly interested in the philosophical ideas of Herbert Spencer and frequently published philosophy articles and letters about atheism and social evolution in journals.

Constance Naden was unique in her approach to education, learning within the male-dominated spheres of science and philosophy, and, instead of working towards a specific qualification, undertook her own programme of study which attended to her own particular interests.

Throughout her life, she brought her distinctive scientific and philosophical interests to her literary works and continuously worked on expanding her knowledge and philosophical understanding of the universe.

Later Life

Naden’s activities later in life demonstrate a keen interest in social justice. After her grandmother died in 1887, Naden inherited a large fortune which gave her the opportunity to travel with her friend Madeline Daniell, a campaigner for women’s rights to higher education, to Europe, India, and the Middle East. On this trip, she raised funds to allow women to study medicine in India. When she returned to England, she bought a house in London and became a key public advocate of social reform. She was an indomitable speaker, lecturing on matters of women’s suffrage for the Central National Committee for Women’s Suffrage and the Women’s Liberal Association. She was also an active member in a range of societies such as the Aristotelian Society and the National Indian Association, and canvassed for the Liberal candidate for Marylebone, G. Leveson-Gower.

Death

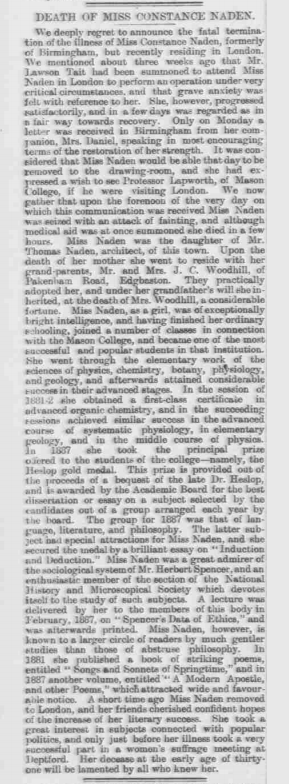

On 23 December 1889, Constance Naden died from complications related to an ovarian cyst infection. Despite her death, aged only 31, Naden’s achievements were impressive and obituaries praised her fierce intellect, poetic craft and activist engagements. In the Birmingham Daily Post, she is commended for her ‘exceptionally bright intelligence’ and academic achievements whilst recognising her renowned literary successes. In the years that followed, Robert Lewis worked hard to posthumously publish a range of Naden’s work including The Complete Poetical Works of Constance Naden (1894) and her prize-winning essay, Induction and Deduction (1890).

‘Death of Miss Constance Naden’ Birmingham Daily Post: Wednesday 25 December 1889

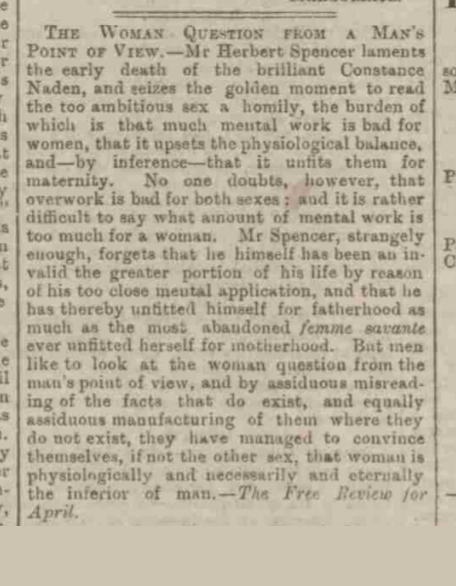

However, an inflammatory letter by Herbert Spencer, a renowned late nineteenth-century thinker, soured these positive efforts to celebrate Naden’s life. In this letter, Spencer praised Naden but suggested that Constance Naden’s ‘mental powers’ were ‘abnormal’ for a woman and would have incurred some ‘physiological cost’. In the late nineteenth century, the topic of women entering high education and engaging in typically male-dominated fields such as Science was highly contentious. Naden’s death became viewed as an example of how a female’s pursuit of knowledge is a threat to their gendered bodies. This caused intense debate and outrage amongst her friends. Over five years after her death, an article was published in Dundee Evening Telegraph critiquing the manipulation of Naden’s death and noting that Spencer himself was ‘invalid’ as a result of his ‘mental applications’.

Herbert Spencer, ‘Letter from Mr. Herbert Spencer to Dr. Lewins. June 10th 1890’, in William R. Hughes, Constance Naden: A Memoir (London: Bickers & Son, 1890), p.90.

Herbert Spencer

‘The Woman’s Question from a Man’s Point of View’, Dundee Evening Telegraph:

Thursday 04 April 1895.

Legacy

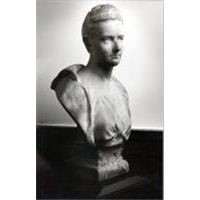

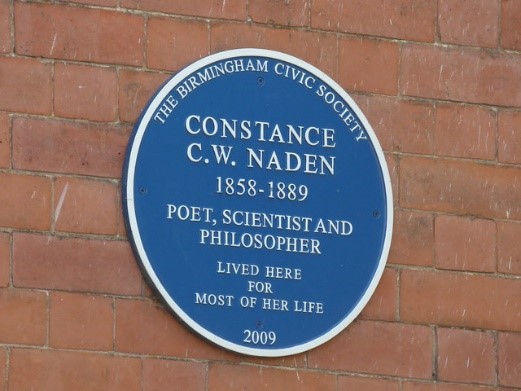

In and around Birmingham, there have been efforts to celebrate Constance Naden’s legacy. At the University of Birmingham’s Cadbury Research Library, Naden is commemorated by a marble bust by William Henry Tyler, and the university itself awards a Constance Naden medal for the best Master’s degree in Arts. In December 2009, a blue plaque was positioned at 20 Charlotte Road, where she lived for most of her life. Finally, before 2019, her grave at Key Hill Cemetery was in practical disrepair. However, due to the efforts of members of her family and Clare Stainthorp, a researcher of Constance Naden’s work, an appeal was set up which led to the full refurbishment of her grave, complete with a quote from Naden’s poem, ‘The Pantheist’s Song of Immortality’ (1881).

It is important that we remember Constance Naden’s drive to succeed in male-dominated spheres and her unique approach to engaging with such an array of activities, from art to science to politics. Her deep intellectual energy and insight makes her one of the most pioneering and talented women of Birmingham and her story an important one to uncover as part of exploring Jewellery Quarter’s Heritage.

Constance Naden Memorial Bust

Blue Plaque at 20 Charlotte Road

Online Talk – Constance Naden: Birmingham’s ‘most gifted daughter’

Online talk given on 20th August 2020, recorded from Zoom.

When Constance Naden died in 1889, at the age of 31, a friend wrote of ‘the sudden and unexpected blow’ depriving ‘the world of a fine and original thinker, Birmingham of its most gifted daughter, [and] progressive Science of a most distinguished worker’. This talk will introduce the life and works of Naden, a fascinating but little-known poet, philosopher and scientist who was born in Edgbaston and buried in Key Hill Cemetery.

Dr Clare Stainthorp is a researcher and writer interested in nineteenth-century poetry, the history of atheism, and the intersections of literature and science. Her first book, Constance Naden: Scientist, Philosopher, Poet, was published in 2019. She received her PhD from the University of Birmingham and now works at University College London. In January, Clare will be starting a Leverhulme Early Career fellowship at Queen Mary, University of London, where she will be researching the nineteenth-century athiest and secular movement for her next book.

Selected Works of Constance Naden

Songs and Sonnets of Springtime. (London: Kegan Paul, 1881)

A Modern Apostle; The Elixir of Life; The Story of Clarice; and Other Poems (London: Kegan Paul, 1887)

Induction and Deduction and other essays (London: Bickers and Son, 1890)

Further Reliques of Constance Naden (London: Bickers and Son, 1891)

The Complete Poetical Works (London: Bickers and Son, 1894): Also available to read online on Victorian Women Writers Project, Indiana University Digital Library Program

Further Reading about Constance Naden

William R. Hughes, Constance Naden: A Memoir (London: Bickers & Son, 1890).

Constance Naden: Grave Restoration appeal website

The Birmingham Civic Society’s ‘Constance Naden’ Article

Clare Stainthorp, ‘Constance Naden: A Danger to Herself?’ in the Dangerous Women Project.org (November 2016).