John Baskerville was a printer, print designer and businessman, who after a series of unusual events came to rest in the catacombs in Warstone Lane Cemetery. He had a fascinating life and an eventful death…

Timeline of Baskerville’s life

January 28 1706(?) – Born at Sion Hill Farm, Wolverley, Worcestershire, England. Not a lot is known of his upbringing, apart from the fact he was raised Presbyterian – but ultimately became a deist – respecting religion, yet also thinking it had been corrupted. He attended Sebright Grammar School. He later on in life became a firmer believer in the separation of church and state. Of his early jobs we know he spent a while as a young man engraving tombstones.

1740 – Started a japanning business in Moor Street, Birmingham, after being introduced to the trade by journeyman cabinet-maker, John Taylor. As someone that was extremely motivated by money this venture ultimately made him a lot of money. Japanning is essentially the process of varnishing metal ware, usually with pictures. Using this money he was able to build a house at Easy Hill. This house no longer exists but was on the site of Baskerville House (built 1938) next to the contemporary Birmingham Library.

1757 – His newfound fortune from the japanning company enabled him to pursue his passion for lettering once again – this time through printing. After setting up a printing house, published his first work, Virgil. This came after beginning to experiment with typefaces and letter founding. ‘Having been an early admirer of the setting of letters I became insensibly desirous of contributing the perfection of them.’ It is important to remember that although Baskerville is very influential within typeface history, he would not have been working alone, rather joined by many Birmingham craftsmen, including the punchcutter John Handy.

1758 – published Lost Paradise by John Milton. This same year the American inventor and philosopher, Benjamin Franklin, visited him, taking Baskerville’s designs back to the United States with him. 1758 is also the year he became printer to Cambridge.

1762 – Printed Horace.

1763 – undertook printing an edition of the Bible (considered his masterpiece) To print an edition of the Bible was a great honour, and Baskerville has needed special permission, granted through a vote, to undertake the task. This role was so important due to the fact people were wary of printers making mistakes or changes that would in turn have an effect on the reading. In his editions of the Bible lists of subscribers can be found (people who donated to his funds to make the project). This once again demonstrated his outreach to the influential people of Birmingham.

1767 – an insert from Baskerville in Birmingham Gazette, about losing his dog:

‘Also lost on Whitsuntide morning a full curled white puppy dog about ten weeks old, the upper part of his head and 9long0 ears of a dark chestnut brown, a large spot of the same colour on his loins, rump and fore legs. Whoever will bring him to the owner shall receive five shillings reward. If not brought home in consequence of this advertisement whoever will give notice where he is so that he may be had again shall receive the same reward and the thanks of J. Baskerville.’

1769 – printed editions of Shakespeare

1770 – printed a 2nd edition of Horace, due to its success ventured on a series of Latin authors. Baskerville’s impact on typeface was pioneering, his composition was different from that of the time, with spaces between the lines and greater margins in the books, his pages were fresh, clean looking and easier to read. He also innovated the pigment of ink used in printing, taking from his japanning it is said his black ink was blacker and shinier than any available at the time.

Personal Life

John Baskerville lived with his lifelong partner Sarah Eaves. After her husband left the country due to fear of imprisonment, Baskerville took Eaves and her four children in, with Eaves to act as his housekeeper. The two soon fell in love and lived as a couple for sixteen years until Eave’s husband died, allowing them to marry, when she was 56 and he 58 (June 1 1764). She acted as a partner with him, and was very much involved in his business life as well.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, reportedly borrowed Baskerville’s name for his Sherlock Holmes story, The Hound of the Baskervilles – Doyle did reside in Birmingham for a while during his lifetime…

Death and Burial(s)

Died 8th January 1775 (aged 68) I couldn’t find the cause of death, only that he died at home at Easy Hill.

He left £500 of his estate to a charity, although the bequest was invalid due to legal reasons. So Mrs. Baskerville was able to profit off this – but instead she paid the money over to the charity.

His request was to be laid to rest, ‘in a Conical Building in my own premises Hearetofore used as a mill which I have lately Raised Higher and painted and in a vault which I have prepared for It. This Doubtless to many may appear a Whim perhaps It is so—But it is a whim for many years Resolve’d upon, as I have a Hearty Contempt for all Superstition the Farce of a Consecrated Ground the Irish Barbarism of Sure and Certain Hopes &c I also consider Revelation as it is call’d Exclusive of the Scraps of Morality casually Intermixt with It to be the most Impudent Abuse of Common Sense which Ever was Invented to Befool Mankind.’

Baskerville penned an epitaph for himself:

Stranger –

Beneath this Cone in unconsecrated ground

A friend to the liberties of mankind directed his body to be inhum’d.

May the example contribute to emancipate thy mind

From the idle fears of superstition

And the wicked arts of Priesthood

The land passed through the hands of Samual Ryland, Esq. and then to Mr. Gibson. During the expansion of Birmingham in the 1820s however, Baskerville’s burial was disturbed as a canal was built through the land of Easy Hill.

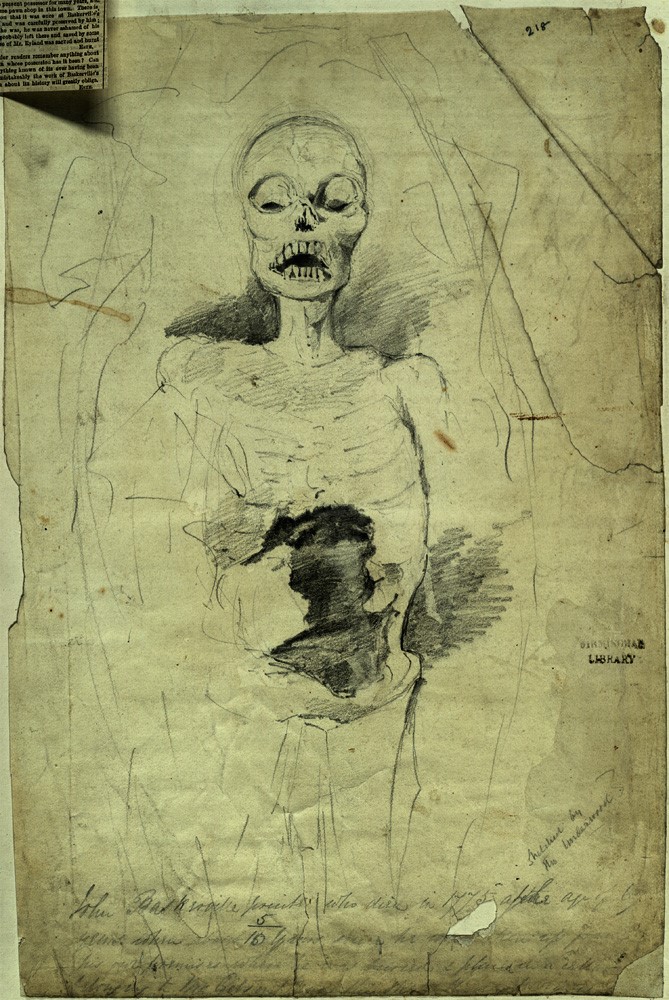

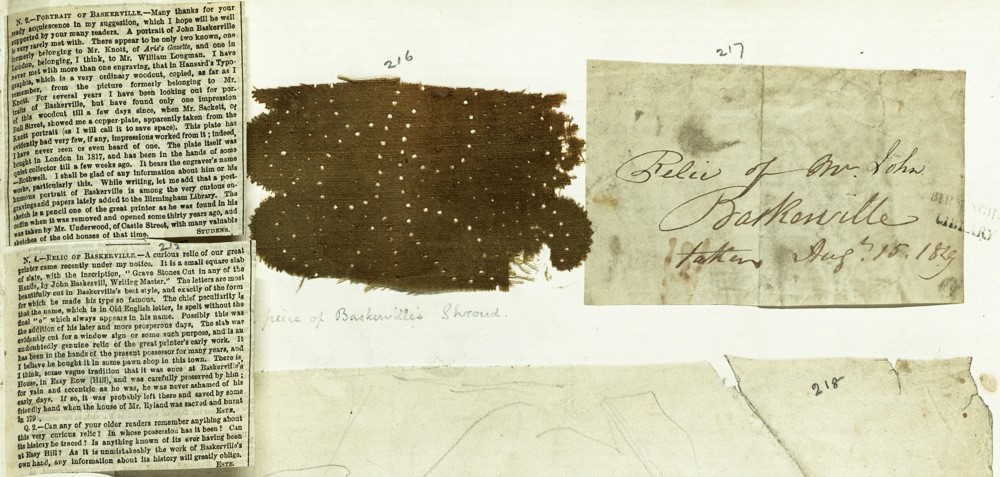

A statement from a newspaper cutting dated May 1828 on the discovery of Baskerville’s coffin:

‘The body was in a singular state of preservation, considering that it had been underground for about 46 years. It was wrapped in a linen shroud, which was very perfect and white, and on the breast lay a branch of laurel, faded but entire, and firm in texture. There were also leaves and sprigs of bay and laurel in other parts of the coffin and on the body. The skin on the face was dry but perfect. The eyes were gone, but eye brows, the eye lashes, lips and teeth remained. The skin on the abdomen and body generally was in the same state with the face. An exceedingly offensive and oppressive effluvia strongly resembling decayed cheese, arose from the body, and rendered it necessary to close the coffin in a short tine, and it was reentered. The putrefactive process must have been arrested by the leaden coffin having been sealed hermetically, and thus access of the air prevented.’

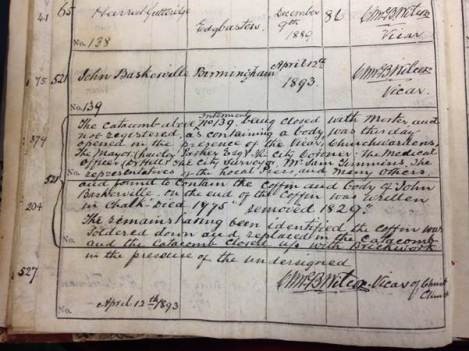

After staying in Mr. Gibson’s cellar the bones were left on display for a number of years following this, although after he was moved it was unknown where he had been moved to for over 70 years. In 1983 he was found in an unmarked vault in Christ Church, New Street.

However this was not destined to be his final resting place as the church was demolished for the construction of Victoria Square. Baskerville, along with other remains from the vaults, eventually made his way to Waterstone Lane Cemetery on 24th February 1898. It seems somewhat ironic that John Baskerville who wished to avoid burial in consecrated ground, should end up in the Church of England Cemetery. We hope that after all the disruption, he’s just glad to have found a place to stay…

Further Information

John Baskerville and the Beauty of Letters, video by History West Midlands

Font Designer – John Baskerville, examples of the Baskerville typography and variations, linotype.com

The Burials of John Baskerville by The Iron Room, Library of Birmingham