In the 19th century, the quality of food and drugs was of great concern. Foods were often adulterated with cheaper ingredients, or coloured and flavoured with poisonous chemicals. Most of this adulteration was done so that cheap food could be sold to the poor and unemployed, but even luxury goods were not guaranteed to be pure. Drugs often contained too little of the active ingredient, or other ingredients to mimic the real drug. Many piecemeal regulations were introduced, but had little effect on the problem. There were International repercussions too. Spain had introduced laws specifically to deal with the contaminated goods arriving from England. At the age of 32, John Postgate started a campaign to address these problems. This campaign would last the rest of his life, resulting in the first legislation with enough power to really address the issues and formed the basis of all subsequent legislation on food and drugs. His life experience had made him fully aware of the issues involved and he was the foremost person to suggest effective legislation and offer practical solutions to the problem.

John Postgate was born at Scarborough, on 21 Oct. 1820 to parents Thomas Postgate, a joiner and his wife, Jane, née Wade. He was the third of nine children, all but one who survived to adulthood. It is likely that the family struggled financially. Thomas probably worked in the shipbuilding industry, which was in decline in Scarborough in favour of tourism. Eleven shipyards operated at the beginning of the 19th century, but had steadily declined to two by 1860. This may have prompted John to leave home, to be apprenticed to a grocer and wine merchant at the age of eleven. He was paid 3/6d (17.5p). While there, He noticed such practices as adding sand to sugar and plaster of Paris to flour. During this time he had taught himself chemistry and in 1834 he was apprenticed to two surgeons, Mr Travis and Mr Dunn, who ran a GP practice in Scarborough. He started on wages of 2/6d (12.5p), but soon he so impressed the surgeons that they advised him to enter the medical profession and articled him to their firm for 5 years. He began to study pharmacy. His leisure hours were devoted to self-improvement, working hard at Latin, chemistry and botany. He often rose at 5am to study. In the summer months he rose even earlier, at 3 or 4am, to gather wild flowers and amassed a collection which he retained till the end of his life. At the age of 17 the Yorkshire Magazine published his paper, “Rare Plants and their Properties”.

After 5 years he completed his apprenticeship and became their assistant, earning enough money to save, with the intention of attending Medical School. After another 5 years, in 1844, he became assistant Apothecary to the public dispensary in Leeds. There, he attended the Leeds School of Medicine. In July 1847 he went to London and sat an examination at the Society of Apothecaries. He impressed the examiners and was given a licence to practice. He obtained a post with a large medical practice in East London and became a student at the Medical College of the London Hospital. In 1848, he became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons which enabled him to work as a GP. He first set up a practice at Kilham, a village in the Yorkshire Wolds. In 1850, after the death of the incumbent GP, Joshua Horwood, he moved six miles south to become a GP in Driffield, a small but prosperous market town.

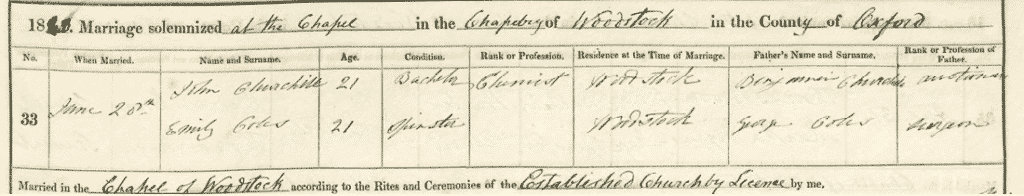

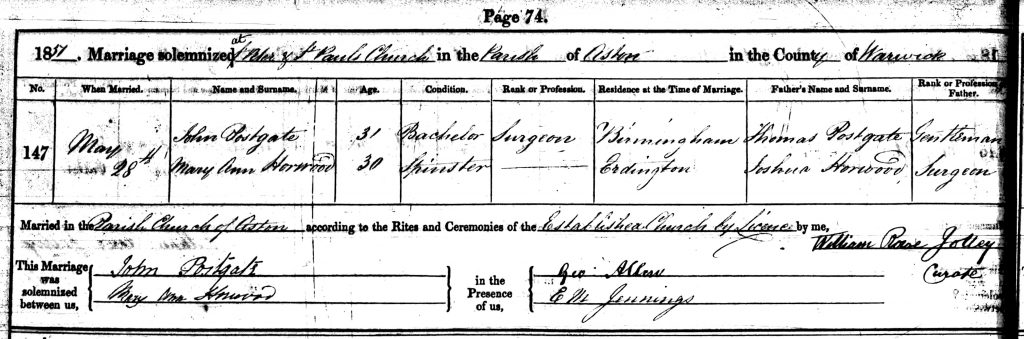

In May 1851, at the age of thirty, he moved to Birmingham, taking Mary Ann Horwood, daughter of Joshua Horwood with him. They were married at Aston Church on the 28th of May.

Note that Mary Ann’s age was stated as 30 years old. Her date of birth is not clear, but she was probably born in 1817, which makes her three years older than her husband.

They moved into 80 Belmont Row, where he opened a GP surgery. They remained in Birmingham for the rest of their lives, moving house several times. Postgate was shocked by the state of the town. In 1852 he published his first pamphlet, “Sanatary Aspects of Birmingham”. This did not deal with food or drugs, but the general state of the town’s infrastructure; the refuse in the streets; the air, which was filled with smoke from the many workshops and factories; the poor state of the drainage and sewage systems. The subject was already of interest to the populace, who had made many protests. The difference between earlier complaints and Postgate’s pamphlet was that he put forward solutions to the problem, suggesting the establishment of a Birmingham Sanatary Society to investigate issues and enforce the existing law on sanitation, and to lobby for further powers. None of his ideas were taken up by the council.

It was the following year, in 1853, that he dropped his endeavours on the general sanitary conditions to concentrate on the adulteration of foods and drugs. His interest had begun as a youth, working at a grocer’s, observing the bad practices that went on. Later, during his studies to become an apothecary, he discovered that drugs could be too weak to be effective, or dangerously impure. As a GP, he saw many patients whose health was affected by the food that they ate. His was not the only voice to address the problem. Dr Thomas Wakeley, founder and editor of the Lancet, published many articles relating to food and drug adulteration. In 1851 he set up the Lancet’s “Analytical Sanitary Commission” to perform chemical and microscopical analysis of food. They published their results, including the names and addresses of manufacturers and tradesmen who had been caught out. These reports were reprinted in the national press, raising much interest and outrage. It was against this background that Postgate embarked on a study of adulteration. He also became an active advocate of laws against food and drug adultery. The adulteration took many forms; powdered alum, gypsum or talc was added to bread to increase the weight and make it whiter; tea, coffee, butter, milk, all the staples, were prey to contamination or substitution; luxury items were faked; old meat and fish sold as fresh; medicines too dilute to work, or containing dangerous ingredients were common; beers, wines and spirits were adulterated or counterfeited; sweets were coloured yellow with lead chromate, green with copper acetate and red with mercury sulphide, all known to be poisonous.

Postgate realised that nothing would happen unless he involved political influence in his campaign. He wrote to William Scholefield, a Birmingham MP, who responded with interest and agreed to further his cause in parliament. On the 26th June 1855, Scholefield moved for a select committee of inquiry in the House of Commons. Postgate was frequently examined by this select committee. Meanwhile, to generate publicity, Postgate held public meetings in the large towns of the north, where samples of bread, flour, ground coffee, mustard, vinegar, pepper, wine, beer, and drugs, adulterated by the local retailers, were exhibited and analysed. He also produced a pamphet, “A Few Words on Adulteration” which stated the problem and offered solutions. Postgate advocated the local appointment of public analysts, coupled with powers given to magistrates to counter such frauds, and his suggestions were substantially embodied in the recommendations of the select committee. Altogether, nine bills dealing with adulteration were introduced into the House of Commons by the members for Birmingham under Postgate’s influence. All these failed due to strenuous opposition from many MPs, merchants and retailers. Eventually, Postgate and Schofield agreed to put forward legislation that would only allow local authorities the option of appointing public analysts, with powers of prosecuting offending tradesmen, rather than compelling them to do so, with the intention of strengthening the law in the future. This was passed in 1860. As expected, it was not very effective, but was eventually strengthened by the passing of the Amendment Act, which became law in 1872. Further suggestions of Postgate’s were embodied in the Sale of Food and Drugs Act of 1875. This legislation was soon followed by similar measures in the British colonies.

John Postgate was a very busy man. While involved in this campaign he carried out his duties as a GP, became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons, lectured at Sydenham College, later becoming professor of Medical Jurisprudence. He assisted in the inauguration at Birmingham of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, a reformist organisation, which started in 1857. Two papers by him on adulteration were published in the ‘Transactions’ for 1857 and 1868 respectively. He had a strong sense of social justice. Politically, he was a Liberal and a reformist. He carried on his campaign despite the many social and personal problems it caused him and his family. He had to deal with intimidation and attempts at bribery by manufacturers, merchants and shopkeepers opposed to his interference. The windows of his house were broken. Once he was shot at. He obtained no public recompense for his services. Travel, pamphlets, postage and other expenses were all met out of his own pocket. This left him with little money to raise his family. His wife, Mary Ann, was an educated woman who had hoped to be a writer. Before John came along she was sought after by many men, but she rejected all of them. Instead of a life of literature, she kept a home and bore seven children on a limited budget. She had to hide the housekeeping money in case it was taken by her husband. Her daughter, Isabella, commented that the union was “hasty and ill-advised”. He also neglected his children, who grew up ‘cordially disliking their parsimonious and seemingly uncaring father’. But to the wider public John Postgate became something of a hero, if feared and disliked by food and drug traders.

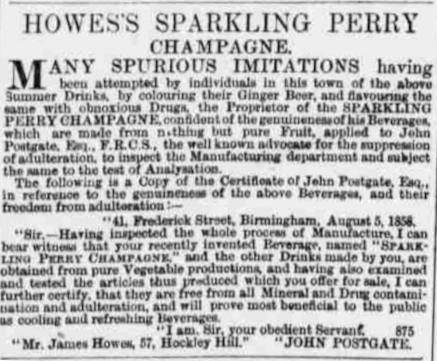

Not all traders opposed his campaign. Some, who were being undercut by rogue traders would send samples of their goods to Postgate, who would write a testimonial to the purity of the product. The manufacturers produced advertisements that were published locally and nationally.

In 1881 he went to Neuenahr, a spa town in Germany, hoping to find a cure for the digestive disorders which he had suffered from for several years. He was taken ill while passing through London on his return and asked to be taken to the London Hospital, where he had done his training. He died of stomach cancer on the 26 September. His body was returned to Birmingham for burial in Warstone Lane Cemetery.

His epitaph records that, for ‘twenty-five years of his life, without reward, and under heavy discouragement, he laboured to protect the health and to purify the commerce of this people.’

It is interesting to compare John Postgate with his American counterpart in food and drug regulation, Dr Harvey Washington Wiley. Wiley was appointed Chief Chemist in the United States Department of Agriculture in 1882. Although his work was fully funded by the American government, like Postgate, he also had to overcome great opposition. The Pure Food and Drug Act did not become law until 1906.

References and further reading

More about John Postgate:

John Postgate, Dictionary of National Biography

Lethal Lozenges and Tainted Tea. A biography written by John Postgate, great grandson.

Guardian review of “Lethal lozenges and tainted Tea”

Pamphlets published by John Postgate:

Sanatary Aspects of Birmingham, 1852

A Few Words on Adulteration, 1857

Medical Services and Public Payments, 1862

Two papers by him on adulteration were published in the Transactions of the Social Science Association, for 1857 and 1868

More on Food Adulteration:

Adulteration and Contamination of Food in Victorian England.

Victorian food: Poisonous buns and other tales.

Further reading: